What to Watch: Penny Dreadful - From Victorian Street Serials to Gothic Prestige TV

Before it was a TV title, a “penny dreadful” was a thing you could buy: a flimsy weekly booklet that cost a single penny, hawked by newsboys and stacked in tobacconists. Eight or sixteen pages, a woodcut on the cover, and a cliffhanger you could feel in your teeth. It was Victorian Netflix—only cheaper, grimier, and gloriously sensational.

The originals: how penny dreadfuls actually worked

London in the 1830s–60s had a recipe for mass thrills: rising literacy, faster printing, and a huge audience of clerks, factory hands, and schoolboys with a coin to spare. Publishers answered with weekly “numbers”—8 (sometimes 16) pages for one penny—packed with crime, horror, and adventure, plus a crude but irresistible illustration on the front. The whole game was serialization: end every installment with a gasp, sell the next one next week.

Two writers loom over the form: James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest, often (and sometimes confusingly) credited on the same titles. Their mega-hit Varney the Vampire; or, The Feast of Blood ran from 1845–47 and helped cement the vampire we recognize today—complete with “fang-like teeth.” Its length in book form? Nearly 900 double-column pages born from pay-by-the-line writing. That’s the spirit of the penny dreadful: breathless, excessive, addictive.

Another icon arrived in 1846–47: The String of Pearls, the first appearance of Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. A trapdoor barber chair, meat pies downstairs, and a tidal wave of readers—pure Victorian Grand Guignol in weekly hits.

If penny dreadfuls had a ringmaster, it was Edward Lloyd, a swashbuckling publisher who courted controversy—he even spoofed Dickens with knockoff serials like Oliver Twiss to hook the same audience at 1/12th the price. Morally dubious? Sure. Culturally decisive? Absolutely: Lloyd built a mass readership for cheap fiction, then parlayed it into newspapers.

By the 1890s, the format was fading, undercut by Alfred Harmsworth’s “halfpenny dreadfullers” and a new ecosystem of boys’ papers. But the template survived—rolling straight into dime novels, pulps, comics, Hammer horror, and our modern screen monster-verse.

The TV series: stitching the old monsters into one story

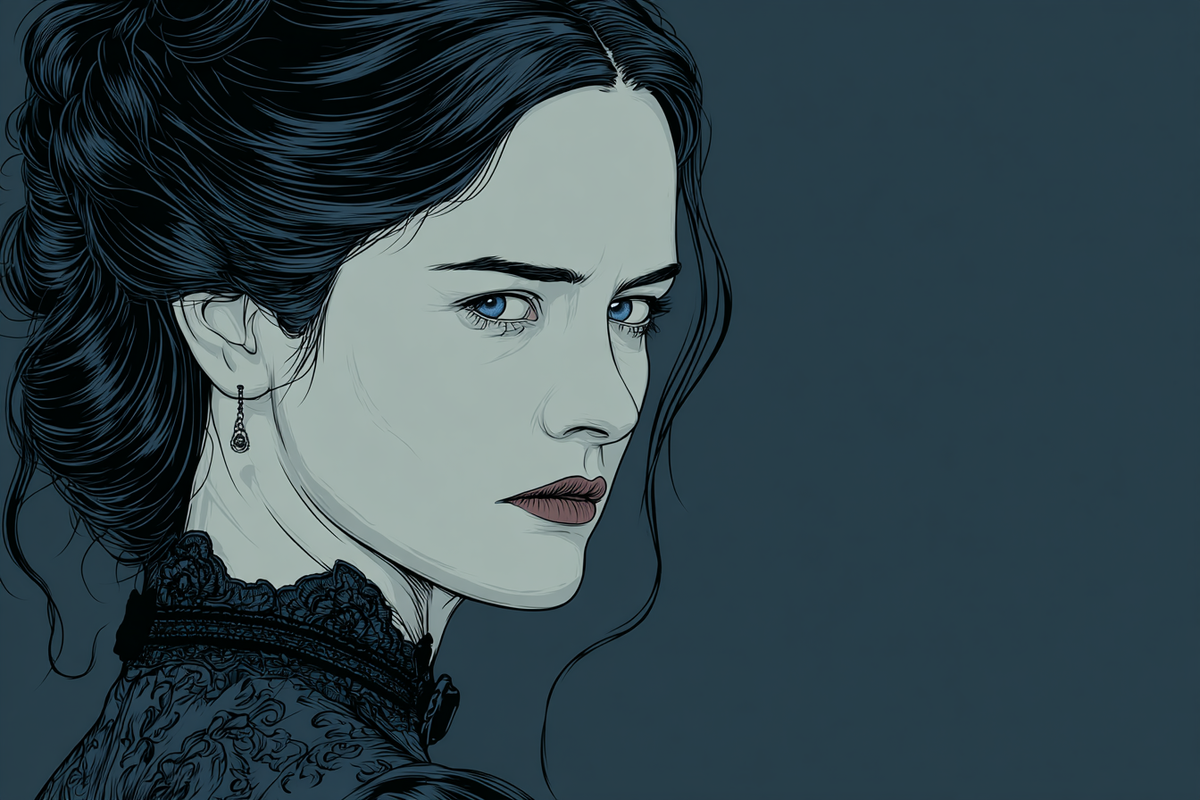

Showtime/Sky’s Penny Dreadful (2014–2016) is what happens when a playwright (John Logan) asks, “What if all those 19th-century nightmares lived in the same London?” Not an adaptation of any single book, the series braids threads from Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Picture of Dorian Gray into an original tale centered on a haunted medium, Vanessa Ives (Eva Green). Logan has described building a shared Victorian world rather than retelling one novel—very much in the collage spirit of penny fiction.

Why it feels “penny dreadful” in spirit:

- Serial rhythm. Seasons play like deluxe installments—each hour ending on moral or supernatural cliff edges that propel you forward, just like the old weeklies.

- Public-domain mash-up. Prest & Rymer once borrowed and recycled tropes freely; Logan does the high-art version, setting Frankenstein’s creature, Dorian Gray, and Dracula-lore on a collision course.

- Grand, lurid craft. Where the originals had woodcuts, the show has cathedrals of production design, operatic scoring (Abel Korzeniowski), and BAFTA-winning make-up/hair and production design.

What the show’s actually about (no spoilers, just stakes)

Victorian London is a crucible. Vanessa Ives wages a spiritual war while drawn to and repelled by dark forces; Sir Malcolm Murray hunts what took his daughter; Ethan Chandler hides a bestial secret; Victor Frankenstein plays god and meets his sorrowful creation; Dorian Gray drifts, dangerous and bored. It’s Gothic romance, faith and blasphemy, friendship and damnation—less “monster-of-the-week,” more found family under a curse. (Early coverage framed Eva Green’s Vanessa as the series’ ferocious center—and that’s still the right read.)

Keep an eye out for literary winks: a copy of Varney the Vampire even appears onscreen, a nod back to the very street serials the title invokes.

How to watch it with the history in mind

- Think like a Victorian reader. Let the show’s cliffhangers work on you. The old weeklies lived on suspense; this series does, too.

- Spot the collage. When Frankenstein’s sorrow, Dorian’s decadence, and Dracula’s hunger intersect, you’re seeing penny-fiction logic: borrow, remix, escalate.

- Enjoy the “woodcuts,” upgraded. Those BAFTA-recognized departments—music, make-up, sets—are prestige-TV answers to lurid Victorian covers: craft that sells the shock.

Sampler episodes (for the full effect):

- “Séance” (S1E2) — the moment the series reveals its soul.

- “Possession” (S1E7) — an intimate chamber of terror.

- “A Blade of Grass” (S3E4) — the show’s masterclass in character and theme.(These are widely highlighted in reviews and retrospectives; dive straight through if you prefer, but these three are the spine.)

Why recommend it now?

Because it does what the best penny dreadfuls did: turn anxiety into art. The Victorians read about crime, monstrosity, and temptation to feel the world changing under their boots. This series uses the same icons to ask modern versions of those questions—about power, faith, desire, and what a soul is worth.