The Search for the Soul: The 21 Gram Theory

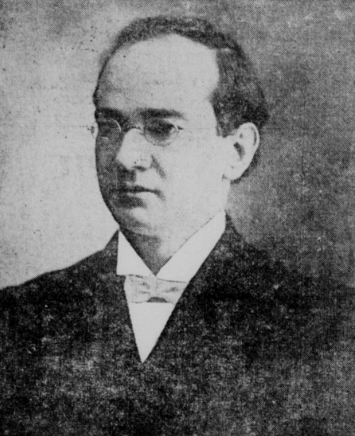

Does the soul have weight? In 1907, a New England physician named Duncan MacDougall tried to answer that with a scale, six dying patients, and a bold hypothesis. His claim—that the human body loses about 21 grams at the instant of death—sparked headlines, debate, and a myth that still lingers more than a century later. What really happened, and what does modern science make of it?

A physician, a scale, and a hypothesis

MacDougall, working in Haverhill, Massachusetts, designed a bed mounted on a large balance scale and placed terminally ill patients upon it as their final hours approached. He reasoned: if a soul is a real, material “substance,” then its departure should register as a sudden, measurable loss of mass. In April–May 1907 he published his report, “Hypothesis Concerning Soul Substance Together with Experimental Evidence of the Existence of Such Substance.”

What he said he found

MacDougall observed six human deaths. The results were inconsistent: small step-changes here, nothing there, a scale that wasn’t fully calibrated in one case, and in one subject a decline he rounded to three-quarters of an ounce (≈21.3 g) at the time of death. He concluded tentatively that a “soul substance” might weigh about 21 grams—but also acknowledged many repetitions would be needed.

He later reported no comparable loss at death in fifteen dogs, which he took as support for a uniquely human “soul.” (Accounts differ on how the dogs were obtained; later retellings allege they were euthanized for the test.)

Why the experiment doesn’t hold up

MacDougall’s study is famous, but it isn’t good science by modern standards:

- Sample size & selection. Six human cases with different illnesses (four with advanced tuberculosis) and uneven procedures cannot support a universal claim. Only one case matched the headline number.

- Instrumentation limits. His scale sensitivity was about 5–6 grams, with acknowledged calibration issues in at least one case—hardly precise enough for quick, small transients, and vulnerable to drafts, temperature shifts, or bed movement.

- Confounders at death. Final exhalations, fluid shifts, muscle relaxation, evaporative cooling, and changing buoyancy from warm air currents can all affect apparent weight on an open balance in a room—not to mention measurement artifacts when attendants touch the bed or patient. Contemporary and modern summaries highlight these problems and the inconsistency across cases.

- Selective reporting. MacDougall discounted cases that didn’t fit, then spotlighted the one that did—classic confirmation bias. Skeptical reviews ever since have treated the 21-gram “average” as a myth born from one cherry-picked result.

Even sympathetic commentators who’ve re-read his paper concede that his apparatus could only speak to large changes, not subtle, fast events—and that nothing like a robust, repeatable 21-gram drop emerged.

How the myth took hold

Newspapers amplified the story immediately—“Soul Has Weight, Physician Thinks,” blared the New York Times. The idea was too enchanting to die: a number you could hold in your hand, a scientific-sounding proof of spirit. Later, the 2003 film 21 Grams popularized the figure again, reinforcing the cultural association between “21 grams” and the soul.

What modern science says about “weighing” a soul

Science neither proves nor disproves a soul; it simply has no reliable measurement for it. Mass is tied to matter and energy; thoughts and memories are information patterns in a living brain. When a person dies, any immediate mass change you can measure must come from physical causes: escaping air and moisture, temperature-driven air currents around the body, tiny movements on the apparatus—not an invisible essence slipping away. Popular explainers and skeptical reviews return to the same point: the 21-gram claim is a historical curiosity, not evidence.

Why the idea persists (and why it matters)

The 21-gram story endures because it offers something our instruments don’t: closure. A number promises certainty in the face of mystery. But the deeper human question isn’t “How heavy is a soul?”—it’s “What makes a life feel weighty?” Memory, meaning, relationships—those don’t sit on scales. They live in stories we tell and rituals we keep.

Reading MacDougall today—without the romance

MacDougall’s experiment belongs to the adventurous, sometimes eccentric fringe of early 20th-century science, when physicians tinkered with new ways to test old metaphysical ideas. It’s part cautionary tale (how headlines outrun data) and part cultural artifact (how science and spirituality have long tried to talk to each other).

If you hear someone repeat, “the soul weighs 21 grams,” know the origin, appreciate the audacity, and then bring the conversation back to what we can meaningfully measure—and what we meaningfully value.