Elizabeth Báthory: The Blood Countess

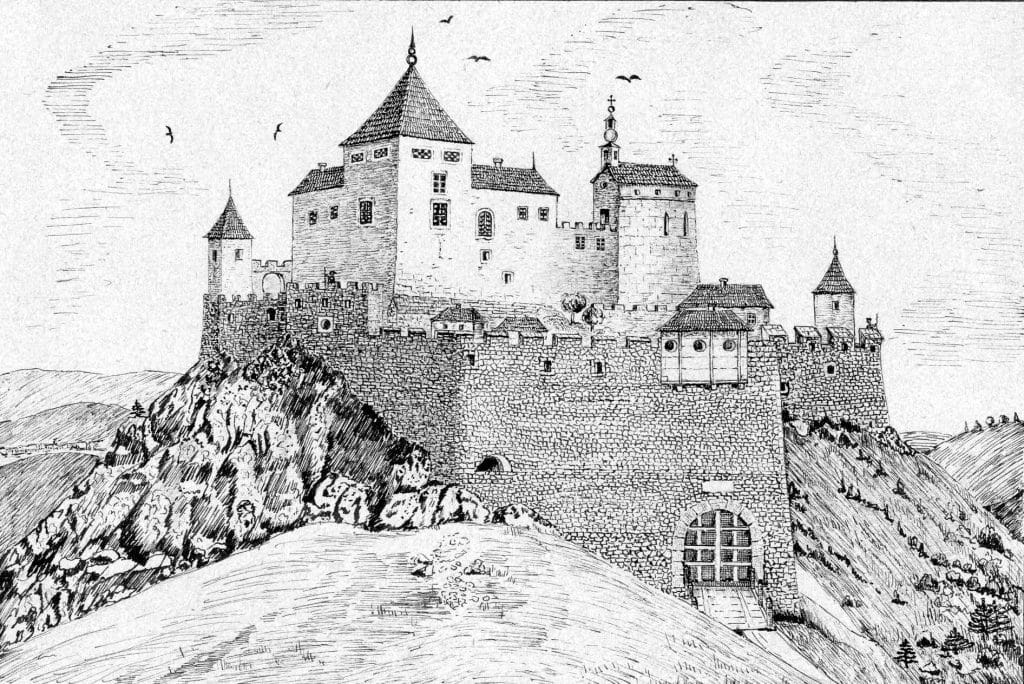

In the hills above today’s Čachtice in western Slovakia stand the ruins of a fortress once ruled by a woman who became Europe’s most infamous villain. Elizabeth Báthory’s story is a tangle of court intrigue, courtroom rumor, and centuries of gothic embroidery. Step carefully: some stones are solid history—others are theatre.

A noble beginning, a dark reputation

Elizabeth Báthory (born 7 August 1560 at Nyírbátor; died 21 August 1614 at Čachtice) was a Calvinist noblewoman from one of Central Europe’s most powerful families—niece to Stephen Báthory, prince of Transylvania and later king of Poland. In 1575 she married Count Ferenc Nádasdy; Čachtice Castle became part of her domain.

Whispers, complaints, and an investigation

After Nádasdy’s death in 1604, rumors that Báthory brutalized servant girls gained force. A Lutheran minister, István Magyari, lodged public complaints; by 1610 King Matthias II tasked Palatine György Thurzó to investigate. Notaries gathered hundreds of depositions—hearsay and rumor among them—building a case that ranged from beatings to murder.

The night of the arrest (and why the dates don’t agree)

Thurzó raided Čachtice at year’s end. Some sources say December 30, 1609; others record December 29–31, 1610. Either way, Báthory was seized along with four servants. Thurzó wrote he found one dead girl and one living “prey,” but the popular image of a countess caught mid-torture is later drama.

Trials without a trial

Báthory herself was never formally tried. Her servants were, in January 1611: Ilona Jó and Dorottya Szentes were burned after mutilation; János Újváry was beheaded and burned; Katarína Benická received life imprisonment. Báthory was confined in Čachtice under strict house arrest until her death in 1614. Reports of a fully “bricked-in room” appear in some narratives, but contemporary clerical visits suggest conditions closer to house arrest than masonry entombment.

How many victims?

Numbers balloon in retellings: 80 appears in some official reckonings; 300+ in hearsay; 650 traces to an alleged private “list” no court ever produced. Much of the testimony was indirect—and confessions from servants were taken under torture, the era’s grim norm. Treat sweeping totals with caution.

The blood-bath that never was

The most indelible image—Báthory bathing in virgins’ blood to preserve youth—does not appear in the 1611 proceedings. It enters print more than a century later, in 1729, via Jesuit writer László Turóczi’s Tragica Historia. Later 18th–19th century authors amplified it; modern historians consider the motif folklore, not evidence.

Politics, debt, and a convenient downfall

Modern reassessments ask who benefited. King Matthias II reportedly owed Báthory a large debt; her arrest and sequestration eased that pressure and allowed relatives and rivals to control her estates. In a region riven by Habsburg–Transylvanian power struggles and confessional tension, a wealthy Calvinist widow made a useful target. None of this proves innocence—but it explains why legend flourished where law was murky.

Where the myth lives on

From Hammer’s Countess Dracula to modern novels, games, and streaming series, Báthory became a pop-culture vampiress—proof that once a story tastes legend, it rarely spits it out.

Visiting the scene

Čachtice Castle is a ruin and tourist site today, its windswept walls overlooking vineyards and scrubby hills—a real place that incubated an unreal legend.

Fact vs. folklore (quick sheet)

- Born/died: 1560–1614; noble Báthory family.

- Accusations: Abuse and murder of girls/women; investigation ordered by Matthias II.

- Arrest: End of 1609 or 1610—sources differ.

- Trial: Accomplices tried/executed 1611; Báthory confined, no formal trial.

- Blood-bath myth: First printed 1729; not in trial records.

The Crazy Alchemist takeaway

In alchemy, appearances deceive: black stages hide bright transformations. Báthory’s legend is similar—truth mixed with projection, fear, and politics until the tincture ran red. When we sift the record, we find a powerful woman, a flawed investigation, and a story that culture transmuted into gothic gold. That’s the real “elixir” here: how quickly rumor calcifies into myth—and how hard it is to distill fact back out again.